Kate O’ Brien and Dr. Maria Gomes

Abstract

Staff in special education settings commonly experience the deterioration and death of students. An inability to cope with anticipatory grief while observing the deterioration of a student can cause burn-out or compassion fatigue which can lead to an overattachment or detachment from the student. Subsequently, an inability to appropriately grieve a deceased student increases the risk of complicated grief which can negatively impact the work of staff. Despite the frequency of death in special education and the risks that grief poses to special educators in their work with remaining students, grief management is not common practice in their training.

This article makes recommendations for school wide actions in supporting grieving staff members which include (i) in-service workshops, (ii) the development of a grief plan (iii) the development of staff support initiatives and (iv) guidelines on support for surviving students after the death of a classmate. Specific strategies are also suggested for staff on coping with anticipatory grief and grief. Such strategies include the five realms of self-care and the cultivation of supportive interprofessional relationships.

Introduction

The advances in life-saving and life-extending technology has seen staff in special education encountering more children with life-threatening conditions1 and more special educators now find themselves providing services to students who have a Do Not Resuscitate Order1. It would appear that experiencing the deterioration and death of a student is inevitable to special education staff (teachers, special needs assistants, administrators etc.).

The most readily available research suggests that between 59% to 70% of educators teaching students with significant impairments have experienced the death of at least one student2, 3. Many of the interviewed professionals had experienced multiple student deaths, and one professional had experienced the deaths of 20 children3. The most recent research in this field notes a potential increase in the number of student deaths experienced by teachers in special education settings4.

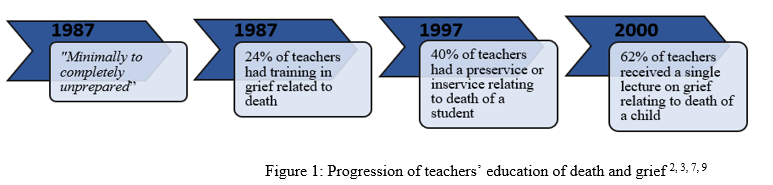

Although much is written about supporting children and families when a child dies, a search of the nursing, medical, psychological, counselling, and educational literature reveals few guidelines for supporting bereaved professionals. Although special education personnel frequently experience grief, the death of a child is not within their normal range of expectations or training5 and they often lack substantial training and support to deal with grief 6, 7. Special educators do report an increase in education in terms of pre-service or in-service training regarding dealing with death and grief (see Figure 1), however research beyond 2000 is scarce, and over the last twenty years since this published research, the advances in life-saving and life-extending technology has seen staff in special education encountering more children with life-threatening conditions8. Therefore, we must question if we are providing substantial information and support for those teaching and supporting society’s most vulnerable children.

Moreover, the school community often lacks a formal support system for staff when the death of a student occurs10 and few schools are reported to have a proactive protocol or plan for dealing with a death10. This lack of a formal system is compounded by the lack of pre-service or in-service education about grief and the grieving process. Educators report receiving more support from colleagues than administrators after the death of a student3, and 83% of educators who have experienced the death of a student report no known source of support2.

The purpose of this article is to provide information regarding the unique grief experienced by special education staff teachers as a result of the deterioration and death of students and to offer suggestions for special schools to support members of staff and the surviving students.

Deterioration of Students and Anticipatory Grief

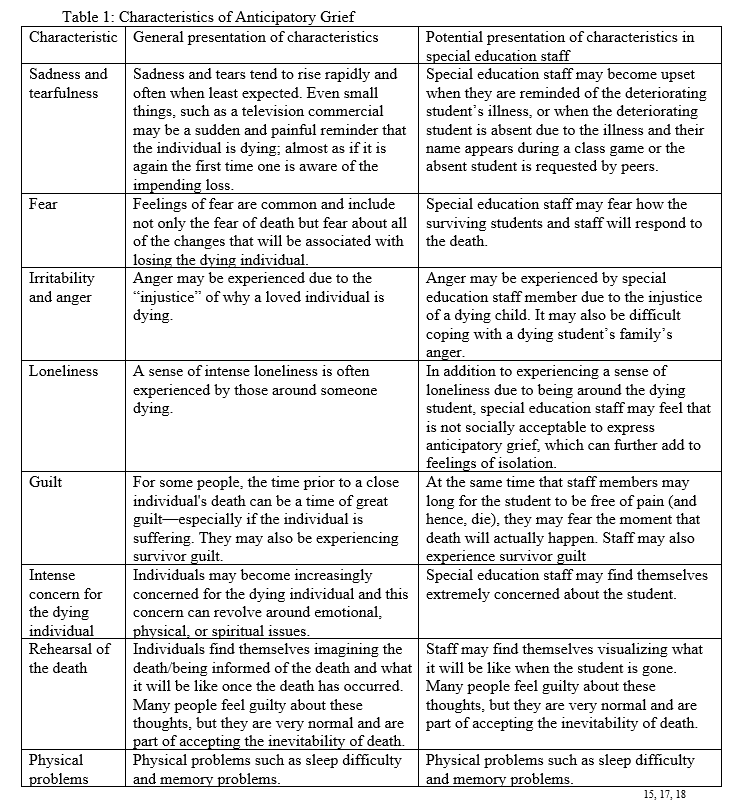

With more children with life-threatening conditions attending schools8, it is plausible that their teachers and supporting staff anticipate their death, which can cause Anticipatory Grief (AG);11, a term coined by American psychiatrist Eric Lindemann12. Lindemann observed that wives of soldiers at war rejected their returning husbands after the war12. This rejection was interpreted in light of Freud’s psychoanalytic theory in which emphasis was placed on “grief work”13. Accordingly, the bereaved inevitably had to work through the emotional pain of the loss and eventually relinquish the bonds with the deceased to avoid adverse bereavement outcome13. Lindeman’s description of AG built on the assumption that the wives had begun their grief work before the loss as the threat of losing their husbands had made them detach their bonds to their husband12. Hence, the concept of AG rose from the notion of Freud’s grief work hypothesis and the necessity of relinquishing emotional bonds seated within a psychoanalytic theoretical frame. Although AG has received substantial interest from clinicians and researchers alike, it remains a little understood psychosocial construct which is seldom recognised14-16, the most commonly cited effects are outlined in Table 1.

Staff who work with deteriorating students and experience AG are at risk for burn-out or compassion fatigue19. Burnout is a response to chronic work-related interpersonal and emotional stressors, and it is measured on three general scales: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and lack of perceived personal accomplishment19. Compassion fatigue involves an excess of empathy and undue identification with the dying individual’s suffering, resulting in an inability to maintain a healthy balance between objectivity and empathy19, which is described as the delicate balance of mutually conflicting demands of simultaneously letting go of, and drawing closer to the dying individual16. Certain professionals develop strong interpersonal relationship with a dying individual and experience a sense of bereavement similar to the family when the individual dies20 whereas other professionals detach themselves from the experience and the dying individual in an attempt to avoid the pain of grief21. Such overattachment or detachment with students is not conducive to a healthy relationship with the deteriorating student. Furthermore, a high AG score (as measured via factor analysis of an composed of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours) is associated with acute anxiety11, high level of post-loss depressive symptoms 22, 23, high self-rated stress 22-24, complicated grief 25, 26 and post loss avoidance 24, all of which negatively impact the work of staff.

Death of Students and Grief

The grief experienced by special education after the death of a student is influenced by many factors 27. Among these determinants of grief are (i) the relationship between the member of staff and the deceased student, (ii) the mode of death of the student, (iii) the age of the deceased impacts the grieving, given it is usually easier to accept the death of a person ripe in years than that of a young person11 (iv) the presence of a support system in the staff member’s life, (v) the religious, social, ethnic, and cultural background of the member of staff, (vi) the staff member’s coping behaviours, and (vii) the staff member’s previous experience with loss, (death/divorce/job change etc).

William Worden’s work with bereaved persons resulted in a move from looking at grief as a stage or phase framework28 to what he considered a more practical approach11 and the grief of staff members and larger school community can be approached as this series of tasks to be faced (see Figure 2)11, 29. There is no set timeline to completing these tasks, although they generally occur over months or years, not days or weeks. Worden points out that while it is essential to address these tasks to adjust to a loss, not every loss we experience challenges us in the same way.

Future Research Inquiry

The available research within the field of grief in special education is dated. Current research regarding the training received by current special educators on grief (lectures, preservice, in-service) and the grief practices of special schools are necessary to inform further support for special education practices. The authors of this article plan to conduct small scale research regarding staff training and school grief practices in conjunction with the piloting of a grief workshop in special schools. Research exploring the grief support in special schools in Ireland would be an incredibly informative addition to the field and will inform best practice regarding this sensitive area.

Those in grieving often do not give themselves permission or time to grieve27 and special education staff may often be required to put their own grief on hold while helping others30. When members of staff experience the death of a student, they must not only cope with their own grief and its accompanying reactions (e.g. anger, guilt, frustration) they may also be expected to support the family of the student31. Moreover, the staff member’s relationship with the student may have failed to be recognised by others or the staff member themselves30. If the bereaved member of staff has failed fully to perform the tasks of mourning identified by Worden, they are at risk of unresolved or complicated grief11, 27, which evidently negatively impacts the work of staff30.

Surviving Students in Grief

In special education settings, staff must support other students who may not fully understand the implications of death and may only know that a classmate is missing32. Given a limited cognitive capacity does not indicate a limited emotional capacity, the surviving students may experience an emotional response through grief when a classmate dies33. The remaining students may present with somatic complaints, relationship difficulties, social withdrawal, increased compulsivity, intensified frustration, and self-injurious behaviour34. It is the responsibility of staff to remain cognizant that such ‘challenging behaviour’ may be expressions of grief rather than an attribute of the intellectual disability35, 36. The challenge to staff is recognising that increased frequency and severity of these maladaptive behaviours indicates recognition that something has changed and the child is attempting to cope with that change37. There can be significant consequences for people with intellectual disability if they do not understand dying and death38.

Recommendations

Many of the Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) strategies employed in the treatment of anxiety disorders and depression, such as graded exposure to avoided or feared situations, increasing pleasant events and challenging unhelpful thoughts, can be modified for working with bereaved people39. Moreover, CBT has been found to be more effective than other commonly practiced therapies when working with bereaved individuals40, 41 and is becoming a commonly employed mode of therapy when working with bereaved42. Therefore, CBT strategies are incorporated into this article’s recommendations for informing school grief practices and supporting bereaved members of staff43. Such strategies include providing information about grief; provision of a structured framework for how to deal with difficulties in the school; basing classroom decisions on evidence not emotions; self-care strategies and ways to challenge negative thoughts.

School Recommendations

Special educators experiencing grief require support from their school in order to continue to work with surviving students without becoming overburdened by loss44. Schools can support staff to cope with the deterioration and death of students through (i) providing in-service grief workshops (ii) developing a grief plan (iii) developing staff support initiatives and (iv) providing guidelines on support for the surviving students after the death of a classmate. Addressing the support needs of the school community could improve job satisfaction and prevent compassion fatigue45, 46.

(i) Provide Grief In-Service Workshops

Individuals working in special education need to acknowledge the possibility of the death of a student1-3, therefore there is benefit to the provision of proactive in-service grief workshops. Such a workshop could focus on the material outlined in this article to include recognizing signs of grief, understanding its impact and guidance as to how special educators can best support themselves and the remaining students after the death of a student47. William Worden’s Tasks of Grief (see Figure 2) 11, 29 may be a particularly helpful approach. In-service workshops should acknowledge and respect differences in staff member’s responses to death, noting the determinants of grief27. Annual in-service workshops may help to establish a culture of openness to talking about death and grief.

(ii) Develop a Grief Plan

Schools can support staff by being proactive prior to a death rather than reactive after the death of a student. Members of staff working with students, along with administrators and counsellors could develop a grief plan with procedures to be implemented following the death of a student. The plan must include support for all staff as well as support for other students and families and should acknowledge the staff member’s role in the life of the child. It is recommended that all staff be involved in the plan’s conception to ensure it reflects their preferences and needs. As part of this grief plan, staff should develop rituals to say goodbye when a student dies (e.g., developing a memory book) and methods as to how they want to remember the student (planting a tree; having an end of the year memorial service for deceased children; inviting families to such a memorial service). The grief plan should include resources for members of staff who had contact with the student who has died and such resources should be a part of the school’s professional library. As with other procedures, the grief plan should be reviewed annually, possibly during in-service training.

(iii) Develop Staff Support Initiatives

Examples of staff support initiatives could include bereavement debriefing and an emotional safety policy. Bereavement debriefing would consist of the provision of supportive sessions for staff in the wake of a death to offer them the opportunity to respond to the student’s death and to contextualise it in the context of their relationship with the student. During each session, the factual circumstances of the student’s death could be reviewed and staff members who knew the student are offered an opportunity to describe their emotional response to the situation, their coping strategies and what they learnt from working with the deceased student. Palliative care staff who participate actively in similar debriefing sessions report an increased ability to manage grief and maintain their professional integrity48.

The creation of an emotional safety policy is to ensure that staff members feel emotionally supported to deal with the unique demands of their work46. The support needs of all staff should be identified and incorporated into this policy. Staff should be able to articulate the type of assistance they need during the initial stages of grief as well as during the extended grief process. Such a policy can specify school strategies to support staff (in-service workshops etc.) and the responsibilities of individual members of staff (e.g. To use rituals to acknowledge one’s own losses and to attend to “grief work;” to maintain careful boundaries; to engage in restorative activities; to maintain a healthy work-life balance; to acknowledge painful experiences).

(iv) Guidelines on Supporting Surviving Students

The death of a student must be addressed in the special education classroom, as there are significant consequences for individuals with an intellectual disability if they do not understand dying and death38. Schools must support their staff in exploring death with students as teachers’ comfort with the topic of death has a direct impact upon their ability to provide a positive environment in which children can explore the concepts of death and dying49-52.

The school should help teachers to understanding each student’s developing conceptions of death, as this will enable the teacher to respond to children’s level of cognitive development as well as their unique individual experiences with death53-56. Moreover, the school should ensure that teachers have familiarity with children’s literature on death57, 58 and provide resources available on explaining death to children with intellectual disabilities34, 37, 59, 60. Table 3 provides key suggestions for special schools to support their students after the death of a peer32, 34, 59, 61.

Staff Recommendations

(i) Anticipatory Grief Guidance

Efficacious facilitation of anticipatory grief is encouraged to reduce the risk of burn-out or compassion fatigue while supporting students who are deteriorating19, 62, 63. Such strategies are outlined in Figure 3. The objective of employing these strategies is not to alleviate anticipatory grief but to facilitate and guide the grieving process for adequate functioning and support at the end of life and post-bereavement62, 63.

(ii) Grief Guidance

The five realms of nurturing oneself (see Table 2) are conducive to coping with grief 64-67.

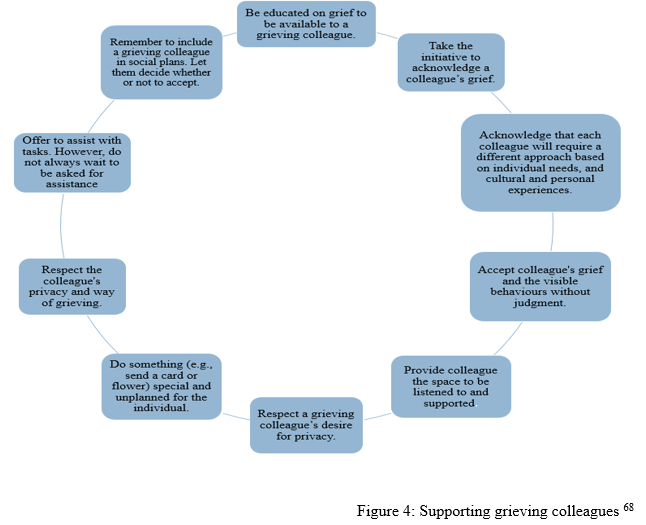

(iii) Cultivation of Supportive Interprofessional Relationships

In order to continue to support surviving students without becoming overburdened by loss, staff may require support from fellow colleagues44. Colleagues can provide assistance for the staff who worked closely with the deceased student. Recommendations for supporting grieving colleague are outlined in Figure 468.

References

- Ashby D. Does Inclusion Include the Right to Die at School? Journal of Cases in Educational Leadership. 1998;1(2):1-8.

- Smith M, Alberto P, Briggs A, Heller K. Special educator’s need for assistance in dealing with death and dying. DPH Journal. 1991;12(1):35-44.

- Bohling V, Reiser B. Death education for personnel in early intervention and early childhood special education. Unpublished manuscript: Portland State University, OR; 1997.

- Cooper J, Foulger A, Willis S, Munson L. Teachers who have experienced the death of student. presented at: Council for Exceptional Children; 2003; Seattle, WA.

- Stepanek JS, Newcomb S, Kettler K. Coordinating services and identifying family priorities, resources, and concerns. Strategies for working with families of young children with disabilities. 1996:69-89.

- Reid JK, Dixon WA. Teacher attitudes on coping with grief in the public school classroom. Psychology in the Schools. 1999;36(3):219-229.

- Pratt CC. Death and dying in early childhood education: Are educators prepared? Education. 1987;107(3)

- Batshaw M. Children with Disabilities. 5th ed. Baltimore: Brookes Publishers; 2002.

- Brownell R, Emberland D. Grief education in preservice early intervention/early childhood special education programs. Unpublished master’s project. Portland State University, OR2000.

- Mahon MM, Goldberg RL, Washington SK. Discussing death in the classroom: Beliefs and experiences of educators and education students. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 1999;39(2):99-121.

- Worden JW. Grief Counselling and Grief Therapy. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1991.

- Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. American journal of psychiatry. 1944;101(2):141-148.

- Granek L. Grief as pathology: The evolution of grief theory in psychology from Freud to the present. History of Psychology. 2010;13(1):46.

- Nielsen MK, Neergaard MA, Jensen AB, Bro F, Guldin M-B. Do we need to change our understanding of anticipatory grief in caregivers? A systematic review of caregiver studies during end-of-life caregiving and bereavement. Clinical psychology review. 2016;44:75-93.

- Patinadan PV, Tan-Ho G, Choo PY, Yan AH. Resolving anticipatory grief and enhancing dignity at the end-of life: A systematic review of palliative interventions. Death Studies. 2020:1-14.

- Rando TA. Loss and anticipatory grief. Lexington Books; 1986.

- Fulton G, Madden C, Minichiello V. The social construction of anticipatory grief. Social science & medicine. 1996;43(9):1349-1358.

- Sweeting HN, Gilhooly MLM. Anticipatory grief: A review. Social Science & Medicine. 1990;30(10):1073-1080.

- Aycock N, Boyle D. Interventions to manage compassion fatigue in oncology nursing. Clinical journal of oncology nursing. 2009;13(2)

- Wakefield A. Nurses’ responses to death and dying: a need for relentless self-care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2000;6(5):245-251.

- Zilberfein F. Coping with death: Anticipatory grief and bereavement. Generations. 1999;23(1):69.

- Levy LH. Anticipatory grief: Its measurement and proposed reconceptualization. The Hospice Journal. 1991;7(4):1-28.

- Levy LH, Martinkowski KS, Derby JF. Differences in patterns of adaptation in conjugal bereavement: Their sources and potential significance. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 1994;29(1):71-87.

- Butler LD, Field NP, Busch AL, Seplaki JE, Hastings TA, Spiegel D. Anticipating loss and other temporal stressors predict traumatic stress symptoms among partners of metastatic/recurrent breast cancer patients. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2005;14(6):492-502.

- Nanni MG, Biancosino B, Grassi L. Pre-loss symptoms related to risk of complicated grief in caregivers of terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of affective disorders. 2014;160:87-91.

- Thomas K, Hudson P, Trauer T, Remedios C, Clarke D. Risk factors for developing prolonged grief during bereavement in family carers of cancer patients in palliative care: a longitudinal study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014;47(3):531-541.

- Rando TA. Grief, dying, and death: Clinical interventions for caregivers. Research Press Company Champaign, IL; 1984.

- Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York: Macmillan; 1969.

- Worden JW. Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner. Springer Publishing Company; 2018.

- Rowling L. The disenfranchised grief of teachers. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 1995;31(4):317-329.

- Small M. A guide for bereavement support. presented at: Council for Exceptional Children; 1991; New Orleans, LA.

- Helton S. A Special Kind of Grief: The Complete Guide for Supporting Bereavement and Loss in Special Schools (and Other SEND Settings). Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2017.

- Kitching N. Helping people with mental handicaps cope with bereavement: A case study with discussion. Journal of the British Institute of Mental Handicap (APEX). 1987;15(2):60-63.

- Kauffman J. Guidebook on helping persons with mental retardation mourn. Routledge; 2017.

- Arthur AR. The emotional lives of people with learning disability. British Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2003;31(1):25-30.

- Oswin M. Am I Allowed To Cry? A Study of Bereavement Amongst People Who Have Learning Difficulties (Book). Souvenir Press; 1991.

- Trueblood S. The grief process in children with cognitive/intellectual disabilities: Developing steps toward a better understanding. ProQuest; 2009.

- Wiese M, Stancliffe RJ, Read S, Jeltes G, Clayton JM. Learning about dying, death, and end-of-life planning: Current issues informing future actions. Journal of intellectual and developmental disability. 2015;40(2):230-235.

- Kavanagh DJ. Towards a cognitive-behavioural intervention for adult grief reactions. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;157(3):373-383.

- Currier JM, Holland JM, Neimeyer RA. Do CBT-based interventions alleviate distress following bereavement? A review of the current evidence. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2010;3(1):77-93.

- Kosminsky P. CBT for grief: Clearing cognitive obstacles to healing from loss. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2017;35(1):26-37.

- Neimeyer RA. The changing face of grief: Contemporary directions in theory, research, and practice. Progress in Palliative Care. 2014;22(3):125-130.

- Morris SE. Overcoming grief: A self-help guide using cognitive behavioural techniques. London: Constable and Robinson . 2008.

- Dean RA. Occupational stress in hospice care: Causes and coping strategies. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 1998;15(3):151-154.

- Wenzel J, Shaha M, Klimmek R, Krumm S. Working through grief and loss: Oncology nurses’ perspectives on professional bereavement. NIH Public Access; E272.

- Huggard J, Nichols J. Emotional safety in the workplace: One hospice’s response for effective support. International journal of palliative nursing. 2011;17(12):611-617.

- Cunningham B, Hare J. Essential elements of a teacher in-service program on child bereavement. Elementary School Guidance & Counseling. 1989;23(3):175-182.

- Keene EA, Hutton N, Hall B, Rushton C. Bereavement debriefing sessions: an intervention to support health care professionals in managing their grief after the death of a patient. Pediatric nursing. 2010;36(4)

- Galen H. A matter of life and death. Young Children. 1972:351-356.

- Fredlund DJ. Children and death from the school setting viewpoint. Journal of School Health. 1977;

- Gordon AK, Klass D. They need to know: How to teach children about death. Prentice Hall; 1979.

- Atkinson TL. Race as a factor in teachers’ responses to children’s grief. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 1983;13(3):243-250.

- Childers P, Wimmer M. The concept of death in early childhood. Child Development. 1971:1299-1301.

- Anthony S. The Discovery of Death in Childhood and After. Hammondsworth. Middlesex: Penguin Education; 1973.

- Bluebond-Langner MH. Meanings of death to children. McGraw-Hill Companies; 1977.

- Speece MW, Brent SB. Children’s understanding of death: A review of three components of a death concept. Child development. 1984:1671-1686.

- Wass H, Shaak J. Helping children understand death through literature. Childhood Education. 1976;53(2):80-85.

- Dahlgren T, Pragerdecker I. A unit on death for primary grades. Health education. 1979;10(1):36-39.

- Hollins S, Sireling L. When dad died. Books Beyond Words; 2018.

- Helton S. Remembering Lucy: A Story about Loss and Grief in a School. Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2017.

- Schaefer D, Lyons C. How do we tell the children?: helping children understand and cope when someone dies. Newmarket Press; 1988.

- Parkes CM, Prigerson HG. Bereavement: Studies of grief in adult life. Routledge; 2013.

- Lebow GH. Facilitating adaptation in anticipatory mourning. Social Casework. 1976;57(7):458-465.

- Ablett JR, Jones RSP. Resilience and well‐being in palliative care staff: a qualitative study of hospice nurses’ experience of work. Psycho‐Oncology: Journal of the Psychological, Social and Behavioral Dimensions of Cancer. 2007;16(8):733-740.

- Jones SH. A self-care plan for hospice workers. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2005;22(2):125-128.

- Wolfelt AD. The understanding your grief support group guide: Starting and leading a bereavement support group. Companion Press; 2004.

- Cohen MZ, Brown-Saltzman K, Shirk MJ. Taking time for support. Oncology Nurse Forum. 2001 2001;28:25.

- Australian Centre for Grief and Bereavement. Bereavement in the Workplace. Accessed April 30th, 2020. https://www.grief.org.au/uploads/uploads/Bereavement%20in%20the%20workplace.pdf

Authors

Kate O’ Brien, Trainee Educational and Child Psychologist, Mary Immaculate College

Dr Maria Gomes, Senior Clinical Psychologist, St Gabriel’s Children’s Services